ELT for Video Games: Language and Video Game Careers

Hello and welcome to another edition of the TESOL Games and Learning Blog. For video gamers, June is a big month as each year the video game industry hosts the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), a 3-day event where the major video game publishers announce their upcoming games. This year, E3 is all digital (12–15 June), and so it is a great time to watch along. It also makes June a great month to highlight just how large the video game industry is and what that means for our students—jobs!

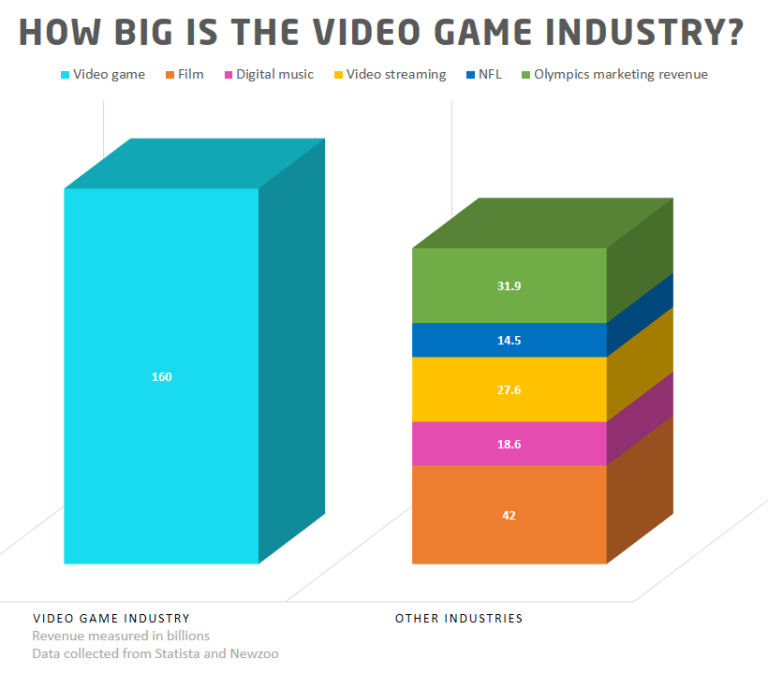

People who are not frequent video game players are often surprised by the size of the video game industry. As educators, we should be aware of just how large the games industry is because it is a frequently multilingual industry with career potential for our students. Estimated to be around US$150 billion a year, the video game industry is 2.5 times the size of the film industry and 5 times larger than the music industry.

Santos (2020) highlights the scale of the games industry in the figure below:

Figure 1. The size of the video game industry compared to other major media industries.

Video Games as a Career

Students interested in making video games a career may find new motivation to study English when they understand how frequently English is a requirement to work at large video game companies. Ubisoft, makers of the Assassin’s Creed series, Rainbow Six Siege, and Rabbids, has offices located around the world, and most job postings, such as quality assurance testing in Kyiv, Ukraine; artist in Chendu, China; and a lead producer in Da Nag, Vietnam all list at least intermediate proficiency in English.

Video Game Localization

Another intersection of video games and language is the area of localization. Localization is the process of contextualizing a game for a specific nation, language, or culture. For example, this would mean taking the Canadian-made game Mass Effect and localizing it for the audience in Brazil. Bondarenko (2018) outlines the following six aspects of localization:

- Translation: the translation of the game’s text and assets from one language into another. It can be performed by one or more people.

- Editing: correcting stylistic and semantic errors, checking translation consistency, and making sure the terminology is correct and consistent.

- Proofreading: correcting spelling errors and other typos. This step often involves working with the text alone rather than within the game.

- Integration: integrating translated materials into the game, changing and adjusting the UI/UX to make sure everything displays correctly, and tweaking the code a little to add the translated materials to the game.

- Regional adaptation: adjusting for regional rules. In China, for example, you can’t show blood, skulls, or any religious symbolism in games. Korea frowns on playing around with religious themes. In Australia, you need to remove all alcohol and drugs from your game.

- Linguistic quality assurance (LQA): testing the quality of the translation and its integration into the game.

Each of the aspects Bondarenko lists require both linguistic and cultural understanding in order to be completed effectively. For many games publishers, this work is outsourced to companies that specialize in localization as the skill set is rather unique.

As educators we should be aware that these specializations exist and consider how we can integrate them into the classroom. In the same way we teach English for tourism or English for business, we should consider how we can offer classes on video game localization.

Until next month, play more games!

About the author

Jeff Kuhn

Jeff Kuhn is the director of esports at Ohio University. He frequently delivers talks and keynote addresses on games and learning, game design, and the need for games literacy in educators. He is one of the founding moderators of the Electronic Village Online’s Minecraft MOOC, a community of practice for teachers learning to use Minecraft in the classroom. He has served on the TESOL CALL-IS steering committee, as the Gaming Special Interest Group chair for CALICO, and in the U.S. Department of State’s English Language Specialist program. His research interests include game-based learning, second language writing, and computer-assisted language learning.