Building Language Learning Games With Scratch

Welcome to another edition of the TESOL Games and Learning Blog! Last month we explored Twine, a text-based interface for creating interactive stories. Twine is a great tool for older students or more advanced language learners, but perhaps not the best choice for younger learners. Younger learners can still engage in the creative process of making games by using Scratch—a visual programming language for making games and animation.

I first discussed Scratch in my “7 Game Design Tools for the Classroom” post from December 2019, but its robust feature set makes it worth exploring in a blog post all its own. Scratch can be used to create language learning games for students to play or introduced into the curriculum so that students can learn to make their own games to share with the class.

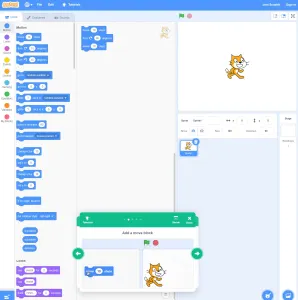

Scratch introduces students to the basics of game development through a color-coded drag-and-drop interface. The fragments of code are color-coded based on the purpose of the code, such as moving a character, changing the look of the game, or adding sound. Students can select the type of code they want to work with then drag it from the left-hand menu into the center coding column, and then test out their code by watching it run in the right-hand column, known as the stage.

Figure 1: The Scratch interface with a pop-up tutorial video series at the bottom center of the screen.

Scratch was developed by the MIT Media Lab as an educational tool. As such, it comes with a wealth of educators guides that can be used by teachers with limited coding experience. Students can find a variety of resources as well to help them in their coding process, including step-by-step resources for making short movies and simple 2D games. Scratch also features a comprehensive video series on YouTube that can be provided to students for self-study or as part of a larger course curriculum.

Scratch also includes a Creative Computing Curriculum. The curriculum is a six-unit course that introduces students to the foundations of Scratch and guides them in coding, animation, making stories, and building games, until finally they are ready for an open-ended project as part of a classroom hackathon. This course could be combined with Google’s free-to-use CS First computer science curriculum that used Scratch as a core component. This includes some interesting 1-hour lessons on creating dialogue, narration, and figurative language that could be implemented into the language classroom.

Scratch has been used to create more than 50 million projects with over a million new projects added every month. This has resulted in a wealth of resources available both on the Scratch website and online that educators can lean on to develop a Scratch curriculum tailored to their students’ interests and abilities. The goal of Scratch is to promote the creative aspects of coding over the technical details of programming. It does so in an inviting, easy-to-use design that teachers and students can use to quickly make their own games.

If you or your students have made games in Scratch, be sure to share them with us in the comments below.

Until next time, make more games!

About the author

Jeff Kuhn

Jeff Kuhn is the director of esports at Ohio University. He frequently delivers talks and keynote addresses on games and learning, game design, and the need for games literacy in educators. He is one of the founding moderators of the Electronic Village Online’s Minecraft MOOC, a community of practice for teachers learning to use Minecraft in the classroom. He has served on the TESOL CALL-IS steering committee, as the Gaming Special Interest Group chair for CALICO, and in the U.S. Department of State’s English Language Specialist program. His research interests include game-based learning, second language writing, and computer-assisted language learning.